The southern Chinese city of Foshan has become the unexpected epicenter of a public health emergency. Since early July 2025, over 7,000 cases of chikungunya virus – a painful, mosquito-borne illness – have erupted across Guangdong Province, with nearly 3,000 new cases reported in the past week alone. Foshan, a metropolis of 9 million people, accounts for 95% of these infections, marking China’s largest chikungunya outbreak since the virus first appeared there in 2008.

The speed of transmission has triggered alarm bells globally. The U.S. CDC swiftly issued a Level 2 travel advisory for Guangdong, urging enhanced precautions for travelers. Hong Kong reported its first imported case on August 4th – a 12-year-old boy who had recently visited Foshan. Chinese authorities, drawing from their COVID-19 playbook, have responded with an unprecedented campaign blending stringent public health measures, innovative biological controls, and mass mobilization reminiscent of past “patriotic health campaigns.”

What is Chikungunya Virus?

The name “chikungunya” originates from the Kimakonde language of southern Tanzania, meaning “that which bends up” – a vivid description of the contorted posture patients adopt due to debilitating joint pain. First identified in Tanzania in 1952, this virus has since spread to over 110 countries, becoming endemic in tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas according to the World Health Organization’s latest fact sheet.

Transmission & Symptoms:

- Spread primarily by infected Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger) mosquitoes – the same vectors responsible for dengue and Zika.

- Symptoms appear 3-7 days after a bite: high fever, severe joint pain (often in hands and feet), muscle pain, headache, nausea, fatigue, and rash.

- While rarely fatal, the excruciating joint pain can persist for months or even years in 30-40% of patients, leading to chronic disability.

- High-risk groups include newborns, the elderly (over 65), and those with underlying conditions like diabetes or heart disease.

Inside China’s Aggressive Response

Facing its first major domestic outbreak, China has deployed a multi-pronged strategy combining surveillance, quarantine, vector control, and community mobilization:

- Hospitalization & Isolation: Infected individuals in Foshan are mandatorily hospitalized in wards equipped with mosquito nets over beds. Patients are only discharged after testing negative or completing a 7-day isolation period – a measure designed to break the human-mosquito-human transmission cycle.

- Door-to-Door Inspections: Community workers in red vests conduct rigorous inspections of homes, demanding residents eliminate all stagnant water sources – from flowerpot saucers and dog bowls to coffee machine trays. Failure to comply risks fines up to ¥10,000 (≈$1,400) or even electricity disconnection.

- Biological Warfare: Authorities are releasing thousands of larvae-eating fish into city lakes and ponds. They are also deploying “elephant mosquitoes” (Toxorhynchites), giant mosquitoes that don’t bite humans but voraciously prey on Aedes mosquito larvae.

- Tech-Enabled Surveillance: Drones scan neighborhoods to detect hidden pools of stagnant water. Pharmacies track purchases of fever, rash, or joint pain medications. Skyscrapers display nightly reminders about mosquito control.

- Mass Mobilization: Governor Wang Weizhong ordered all officials to mobilize citizens for intensive cleaning campaigns – clearing rooftops, courtyards, and installing window screens and bed nets, evoking memories of past Maoist-style public health drives.

While effective in reducing mosquito breeding, these measures have sparked public frustration. Residents report workers entering homes without consent and destroying plants. On social media, many question the necessity of such stringent tactics for a non-contagious disease.

Why is This Outbreak Happening Now?

Several factors converged to create this perfect storm:

- Imported Case & Local Vectors: The Chinese CDC confirmed the outbreak began with an imported case triggering local transmission in early July. Crucially, the invasive Aedes albopictus mosquito – capable of transmitting the virus – is well-established in southern China’s warm, humid climate.

- Climate Impact: Rising global temperatures and recent heavy rainfall associated with the typhoon season have created ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes and expanded their geographic range. “Mosquitoes don’t need a lake. They can breed in a Coke bottle cap,” noted Prof. Ren Chao, a University of Hong Kong expert on climate change and vector-borne diseases.

- Immunologically Naive Population: Unlike regions where chikungunya is endemic, the Chinese population lacks widespread immunity, making rapid transmission possible once introduced.

A Growing Global Threat

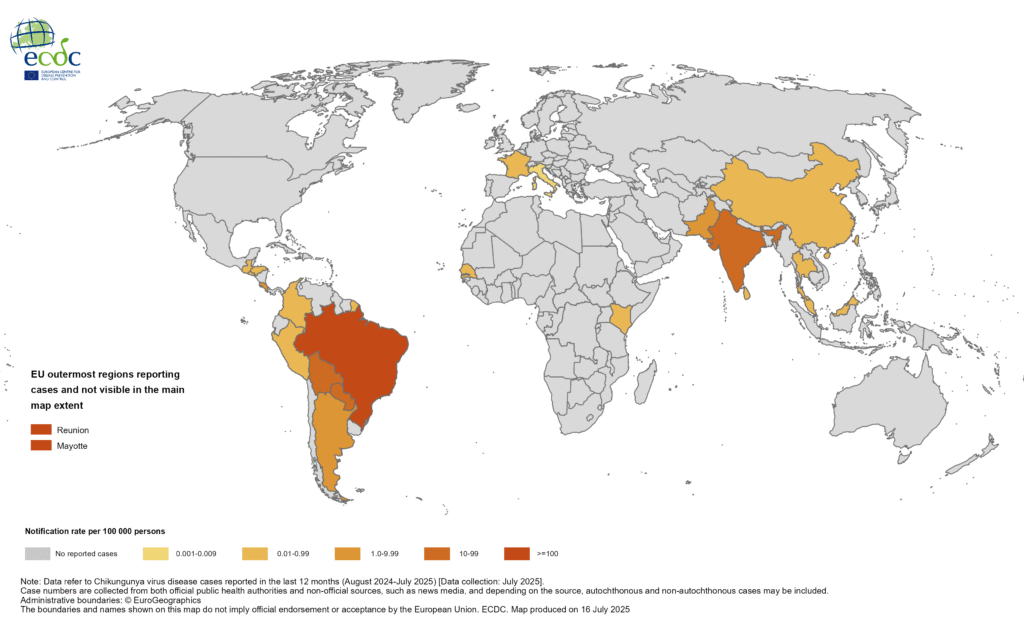

The Foshan outbreak is not isolated. The World Health Organization (WHO) issued an urgent global alert on July 22nd, warning of history repeating itself – referencing the devastating 2004-2005 epidemic that infected nearly half a million people, primarily on Indian Ocean islands, before spreading worldwide.

- Indian Ocean: Reunion Island reports one-third of its population infected since early 2025. Sustained high transmission continues in Mauritius and Mayotte.

- Europe: Continental France has recorded approximately 800 imported cases and 12 local transmission episodes since May 1st. Italy also reported local transmission.

- Americas: Over 250,000 suspected and confirmed cases were reported in the Americas in 2022 alone. The CDC notes ongoing outbreaks in Bolivia.

- Global Reach: The WHO estimates 5.6 billion people across 119 countries now live in areas at risk from chikungunya – a staggering reach driven by climate change, globalization, and the adaptability of Aedes mosquitoes.

Risks During Pregnancy: New Evidence Emerges

Adding urgency to outbreak control efforts, a landmark registry-based cohort study published in Nature (August 5, 2025) analyzed nearly 7 million live births in Brazil (2015-2020), providing robust evidence of significant risks associated with symptomatic chikungunya during pregnancy. The full study reveals critical findings for maternal and neonatal health.

Key Findings for Chikungunya:

- Increased Risk: Symptomatic maternal infection was associated with significantly higher risks of:

- Preterm birth (10% increased risk)

- Low Apgar score at 5 minutes (44% increased risk)

- Neonatal death (50% increased risk)

- Trimester Matters: Risks were highest for infections occurring during the second and third trimesters. Third-trimester infections also showed an unexpected increased risk of congenital anomalies, warranting further investigation.

- Compared to Dengue/Zika: While Zika showed the strongest associations (especially congenital anomalies), chikungunya posed clear, independent dangers, particularly regarding neonatal mortality and morbidity.

This underscores the critical need for pregnant women in outbreak areas to take extreme precautions against mosquito bites. The U.S. CDC specifically advises pregnant travelers to reconsider visiting affected areas like Guangdong, especially near delivery time, due to the risk of mother-to-child transmission and severe neonatal illness.

Prevention and Protection: What You Need to Know

There is no specific antiviral treatment for chikungunya. Management focuses on relieving symptoms with rest, fluids, acetaminophen/paracetamol (avoiding NSAIDs initially due to potential bleeding risks, especially if dengue is also circulating).

Prevention is Paramount:

- Mosquito Bite Avoidance:

- Use EPA-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, or oil of lemon eucalyptus on exposed skin and clothing.

- Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants, preferably treated with permethrin.

- Ensure windows and doors have screens. Use air conditioning.

- Use insecticide-treated bed nets (especially during daytime resting).

- Eliminate Standing Water: Empty, scrub, cover, or discard any items that hold water weekly (buckets, planters, toys, tires, birdbaths).

- Vaccination (Emerging Option):

- Two vaccines (IXCHIQ and VIMKUNYA) are now licensed in the U.S. for adults/adolescents at risk, particularly travelers to outbreak areas.

- Availability is currently limited outside the U.S. The WHO is reviewing data to inform global recommendations.

- Important Note: The CDC currently advises against using the IXCHIQ live-attenuated vaccine in people over 60 due to ongoing investigations into reports of serious adverse events in this age group.

The battle in Foshan highlights the complex challenge of controlling a mosquito-borne virus in a densely populated urban environment. While China’s aggressive tactics may slow the outbreak, long-term success hinges on sustainable vector control, community engagement, improved surveillance, and equitable access to effective vaccines globally.

The Foshan outbreak, coupled with intense transmission in the Indian Ocean and emerging European cases, is a stark reminder under climate change. Chikungunya is no longer a distant tropical concern. As WHO’s Diana Rojas Alvarez warned, “We are seeing history repeating itself.” Vigilance, innovation in vector control and medical countermeasures, and global cooperation are crucial to prevent the bending ache of chikungunya from becoming a far more widespread reality. Travelers should monitor the CDC’s travel health notices for real-time updates on affected regions.